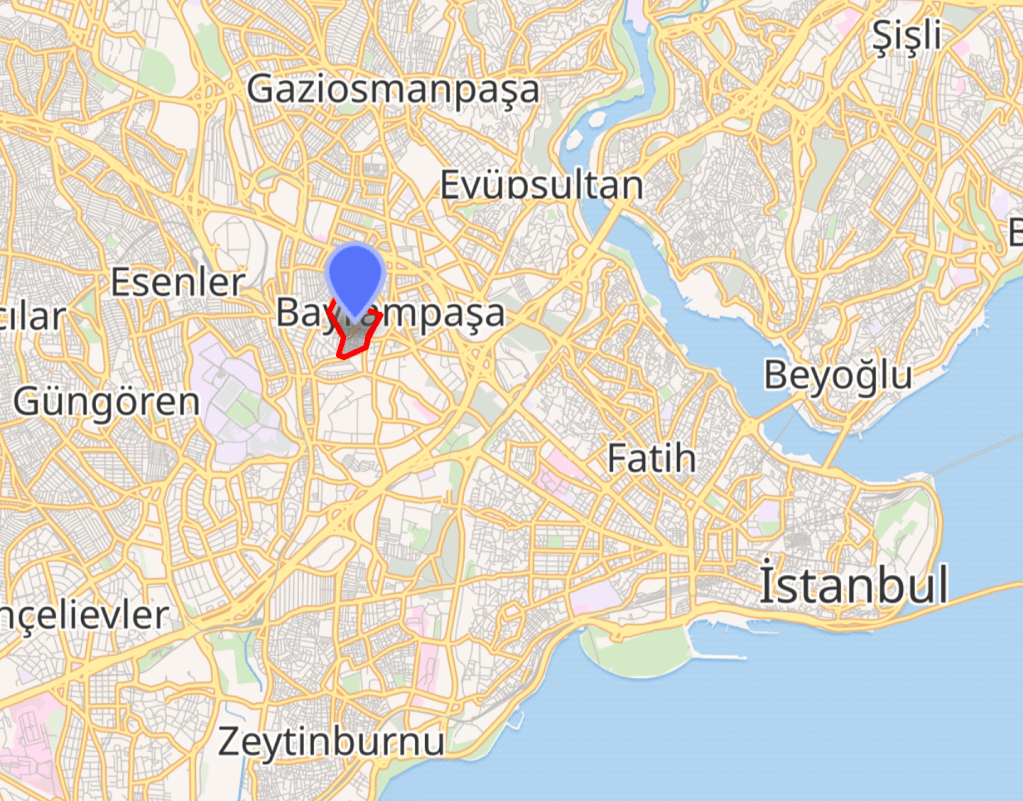

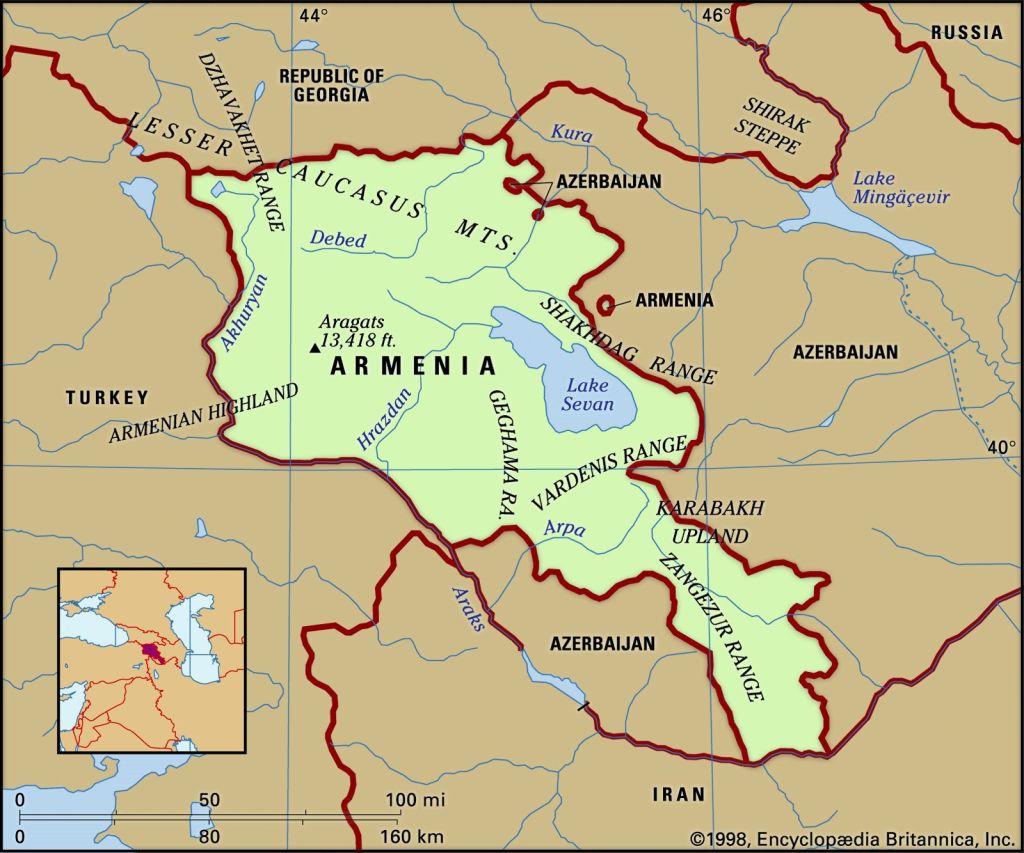

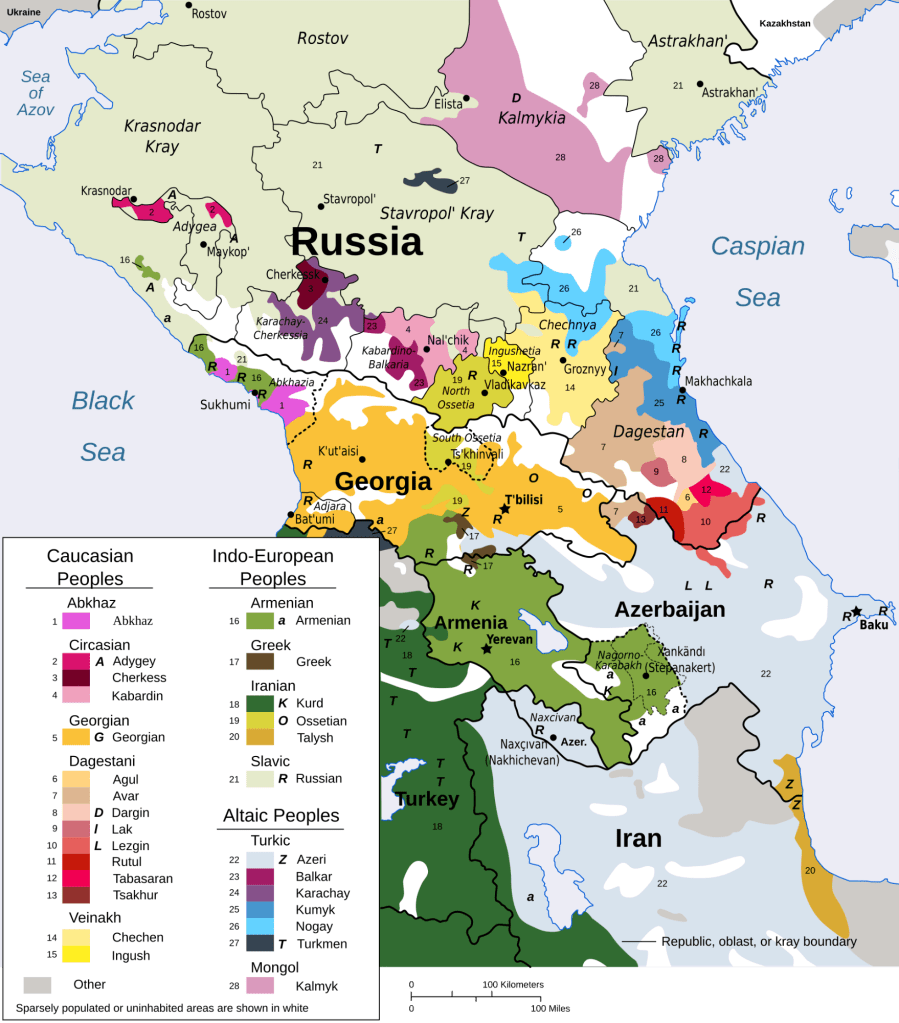

Turkey seems like quite a big place after spending time in the Caucuses. If you combined Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan into one country, Turkey would still be over four times the size (also, good luck trying to govern that imaginary country – it lasted only 36 days when they gave it a go in 1918). Even the shortest route from the Georgian border to Istanbul would be over 1,500km, but also potentially quite dull from a cycle touring perspective.

(credit: Nations Online Project)

As the land connecting Europe to the Middle East and straddling both the Mediterranean and Black Sea, Turkey has for a long time been where East meets West. Alexander the Great, the East Roman Empire, and the Ottomans have all made their mark in what is now the Republic of Türkiye, where the capital Ankara is eclipsed by the behemoth that is the city formerly known as Constantinople, Istanbul.

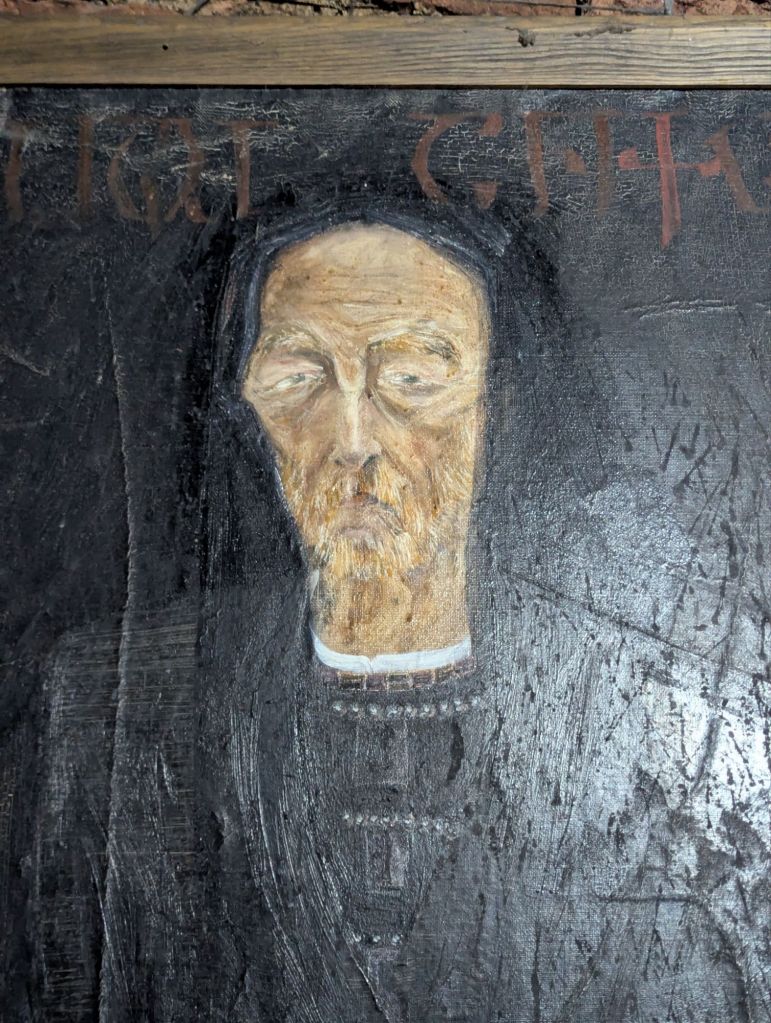

Turkey is also one of those places where it’s quite common to come across portraits of glorious leader, but he’s not alone. There are two men whose faces crop up quite a lot in this country:

- Mustafa Kemal Atatürk: the founder of modern Turkey in 1923 (died in 1938)

- Recep Tayyip Erdoğan: the current president of Turkey (alive)

I can’t claim to have known very much about either of these people before entering Turkey, but with six weeks to go before being allowed back into the EU, I was about to be immersed in this complex and politically volatile country, so there’d be plenty of time to learn.

Over the border

The rumours of Turkey having much better roads than Georgia were absolutely true. I’d gone from weaving between giant water-filled potholes on a glorified dirt track to a pristine dual carriageway, with a generously wide ‘shoulder’ of tarmac outside of the white line – ideal for cycling. That said, the road was so quiet by 7pm you could cycle down the middle of the dual carriageway doing a no hander whilst flapping your arms pretending to fly, if it tickled your fancy.

The sun had set and the cool evening air was oscillating to the chorus of crickets in the long grass. The Islamic call to prayer rang out from loudspeakers of distant mosques, echoing through the valley and sliding slightly out of sync by the time the words reached my ears.

It had been an eventful day, but also quite a long and energy sapping one, so rather than mess around pitching a tent in the dark my plan was to roll into the nearest town and find a hotel – a simple task in Armenia, but Turkey would not always make things so easy. For a start, booking.com – which is stacked with B&Bs in Armenia and Georgia – is blocked in Turkey, and at the time I didn’t realise you can circumvent this by using a VPN, so I resorted to Google Maps.

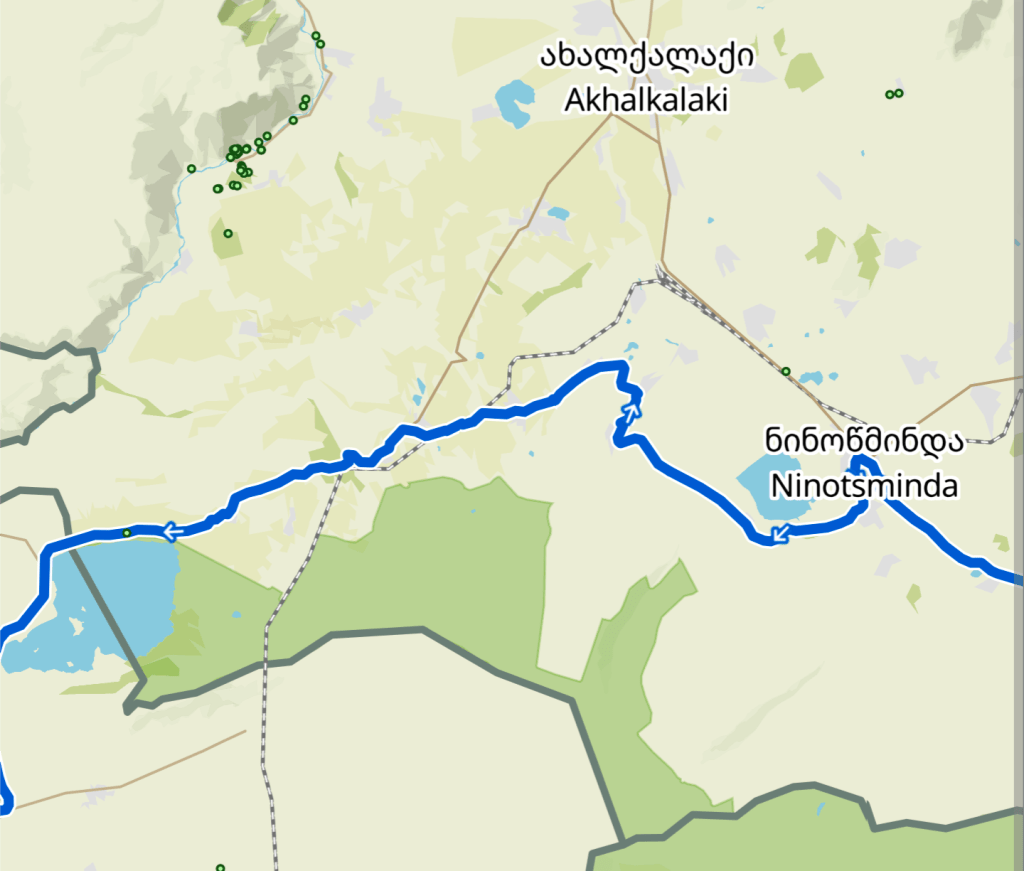

Çıldır isn’t really designed for the passing tourist, it is a small provincial town and eerily quiet at 8pm on a Tuesday evening. I stocked up on snacks from the one shop that was still open, concluded there was no accommodation in the centre that wasn’t either falling to pieces or simply mislabeled nonsense on Google Maps (not uncommon in the Caucuses), and headed for what seemed to be a genuine hotel a few kilometres out of town towards Çıldır lake. The absence of lights gave a very ‘closed vibe’ on arrival, but to my relief Lake Çıldır Lodge was very much open. Quite swanky by cycle touring standards, but at more than double the price of B&Bs in Armenia, I knew the tent would have to make a comeback sooner rather than later.

Lake Çıldır

Judging by the silent hallways and empty restaurant at breakfast, I was the only guest in Çıldır Lodge that night. I’d heard wealthy Turks come to Eastern Anatolia on the train from Istanbul, but perhaps they don’t always make it out of the cities and skii resorts into the smaller towns and villages. With no other guests to distract them the staff made me feel like a guest of honour, with the smiley receptionist insisting on helping to retrieve my bike from the BBQ area despite her obvious phobia of the frogs that had emerged from a nearby pond, shrieking as one leapt from the long grass onto the path. Dedicated hospitality.

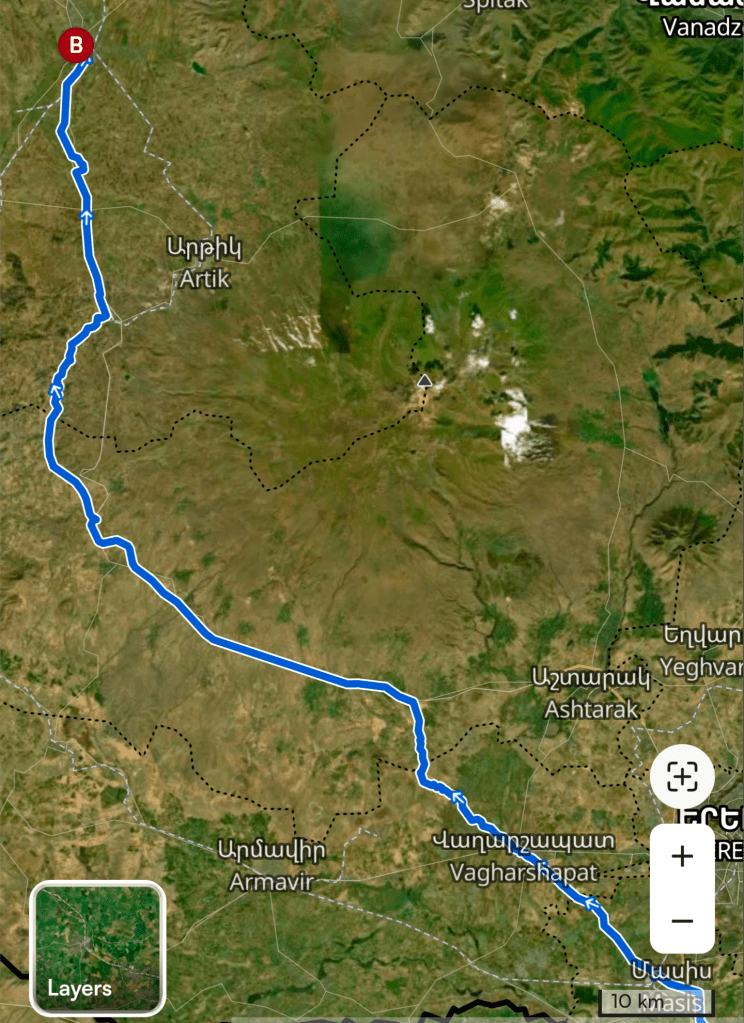

With absolutely no plan whatsoever in place for how I would cross Turkey, heading for the nearest city to take stock seemed like a sensible option. I wanted to generally avoid the Black Sea coast where possible (having heard too many stories of how unpleasant this route is for cycle touring), so I looked for somewhere inland – Kars was a day’s ride away around 80km south of Çıldır, including a gravel section that follows the west bank of lake Çıldır.

Setting off at the leisurely hour of noon in modest temperatures, about four minutes into the ride a plume of smoke caught my eye. It was emerging from an area of land beside the road but obscured from view, so I pulled over to try and see what was burning.

You don’t really get proper ‘dumps’ anymore in Britain – an area of land set aside for dumping rubbish, with no staff or systems in place to contain the leaching fluids or noxious odours. Whether the waste at this site caught fire by accident or was being burnt to make room for more rubbish, who knows, but the smoke can’t be doing much good for the local air breathing population (especially that one dog going full silhouette in the fumes..).

Not quite the introduction to Turkey I was expecting, but I was relieved the two dozen resident dogs didn’t seem overly protective of their adopted home. The pack were mostly rummaging for edible scraps amongst the smouldering waste, with one ambitious (and presumably quite peckish) mutt taking its chances on the bloated carcass of a dead cow.

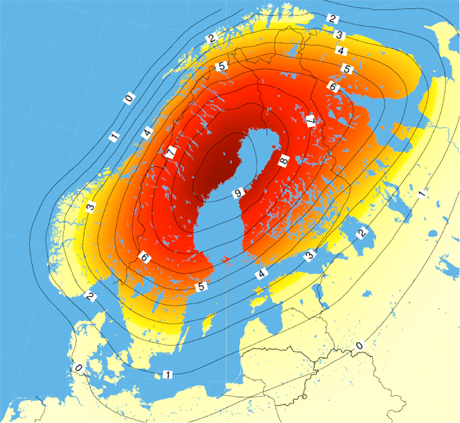

Lake Çıldır looks quite small on a map of Turkey – it’s that little blob in the north east corner on the map above. I expected something along the lines of a Derwent Water, but Çıldır was over twenty times the size – as long as Windermere but much broader. The gravel started off in good shape, but it often degraded into awkwardly large loose stones that jolt the bike in unwanted directions.

Not long after joining the gravel track my presence caught the attention of a large dog that was laying in the yellow grass beside the road. It had a creamy-yellow coat fading to black around the nose, cropped ears, and a booming deep bark – all hallmarks of the infamous Turkish shepherd dog breed: the Kangal.

Kangals

Said to have the most powerful bite of any dog, these fearless guardians have been bred to fight off the likes of wolves and anything else they consider a threat to the flock. Kangals often have cropped ears and wear collars with 3-4″ long steel spikes around their neck, ostensibly to defend against wolf bites, but with the added bonus of making them look really quite intimidating to any prospective sheep rustlers. Learning to accept the inevitable confrontations and deal with Kangals (and other breeds of shepherd dog) is an essential Scout badge for any cyclist passing through Turkey.

The dog was not best pleased by my arrival, communicated quite clearly by the enthusiastic and booming deep barks being broadcast from the roadside protest. It looked like quite an old dog, perhaps retired from duty given the notable absence of any sheep around, maybe this was more ‘grumpy old git’ behaviour than active shepherding. On this occasion I tried the Keep Calm & Carry On technique, which is to say I ignored the dog altogether (no speeding up, no shouting, no stopping).

If any aeroplane landing you can walk away from is a good landing, then any Kangal encounter where you don’t get bitten is a good encounter: this was a good encounter, but there was room for improvement.

Lake Çıldır to Kars

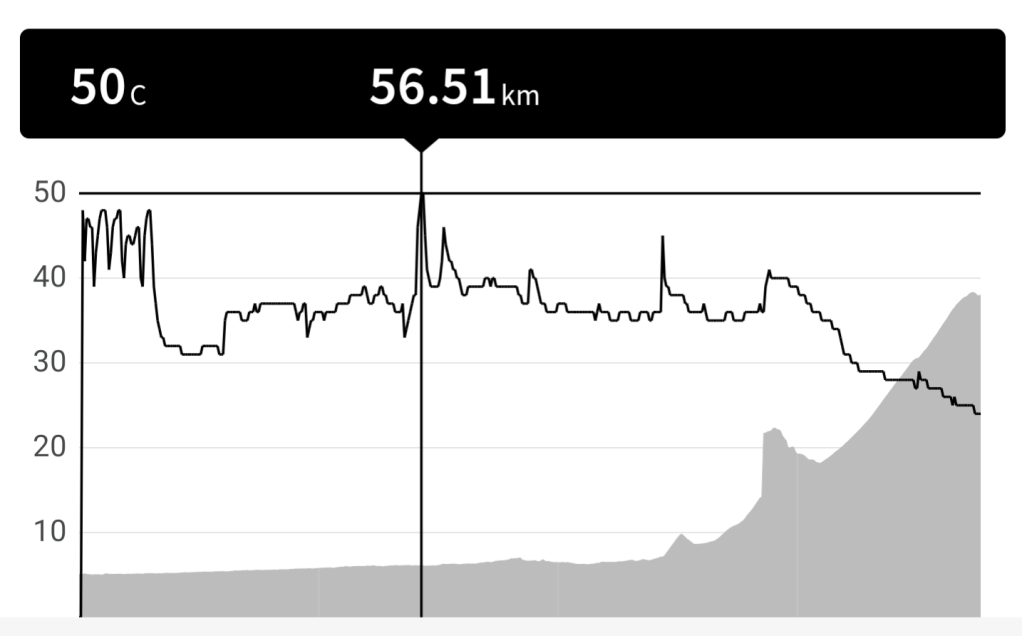

Leaving the lake behind I was once again onto beautifully smooth tarmac roads, winding and weaving through the high mountain plateau. The city of Kars is at a lower altitude than Çıldır; rather than follow a long sequence of hairpin turns, the road becomes like the main drop on a rollercoaster and simply makes a beeline for the lower level – add in a tailwind and you’ve got the recipe for going a little faster than usual. I clocked over 70km/h, which on something so comically un-aerodynamic as my loaded bicycle, is quite the white-knuckle experience.

The weather had been overcast but dry for most of the day, until around 3pm the heavens opened and a heavy downpour rolled in. Pulling off the busy road and stashing under some trees along a riverbank to eat lunch, I noticed several dogs of varied magnitude patrolling the vicinity of a nearby farmhouse. Sure enough, as I began to walk the bike back towards the road to depart, the little yappy one spotted me and raised the alarm.

Within seconds an untethered Kangal leaps up onto the farm’s dry stone wall then down onto the road next to me. I don’t know if it was the excessively aggro barking and snarling, or the fact it wasn’t even a shepherd but just a guard dog allowed to run amok, but I was left feeling pretty annoyed at this mutt. As we approached the end of the street around 20m from the farm, the vigour began to drain from its bark and the dog began to lose confidence in its conviction. I swung around and summoned the energy of my old secondary school’s deputy head and de facto Chief of Justice: Mr Dix, and bellowed:

“Will you just F**K OFF!!”

To be fair I don’t think Mr Dix used to swear at students, but his full volume dressing downs were the stuff of legend. The Kangal instantly backed away like a family dog caught shredding its master’s socks, followed by the smaller dog. The two proceeded to potter around sniffing the floor as if nothing had happened. Would it have still backed off if I’d yelled earlier, when we were closer to the property? I have no idea, but it felt good to let off some steam.

The city of Kars

It had been a while since I’d ridden through a city, which always requires some extra vigilance amongst the weaving scooters, swinging car doors, and drivers pulling out regardless of whether it was a ‘good time’ to do so. It began to feel quite claustrophobic in the crowded city centre streets, so I left behind the street vendors and traffic and made my way onto the open plaza that sits below Kars Castle; when arriving in a new city it’s worth finding a peaceful corner to sit and gather yourself, especially after a long ride.

The hotel I’d booked was one of the cheapest on booking.com (accessed with a VPN), at about £18 per night. Always a gamble going for the cheapest: the building was in need of renovation with weird quirks like the only power socket being 4 feet up a wall, and the shower head blasting off as soon as the water began to flow (transforming into an out-of-control hose & spraying water in all directions). The hotel also happened to be next door to a substantial mosque, where the Fajr early morning prayer rang out from loudspeakers long before my alarm clock.

The cheerful trio of women working reception more than made up for the hotel’s flaws, where I was plied with small plastic cups of chai whilst they practiced their English on me and I waited for the rain to stop.

Kars is far from an ultra modern city but compared to the surrounding small towns and villages it has many more western comforts to offer. There are coffee shops, corporate fast food, and good sized supermarkets. The city also has an abundance of cheese and honey shops flogging the local produce, so many in fact I wondered how they made money given the lack of visible customers.

If you want a cosy café to sit and drink tea in Kars then you can’t go far wrong with Çayloveyou Cafe, where I amused the local punters by trying to eat a handful of sunflower seeds without shelling them first (a bit like eating splinters of wood).

One of the errands on my ‘to do’ list whilst in Kars was to come up with a route plan for getting across Turkey. Istanbul would undoubtedly be the final destination, but rather than just follow the Black Sea coast the prospect of heading deep into central Anatolia seemed more appealing, especially if the route could pass through the bizarre, fairytale-esque rock formations of Cappadocia.

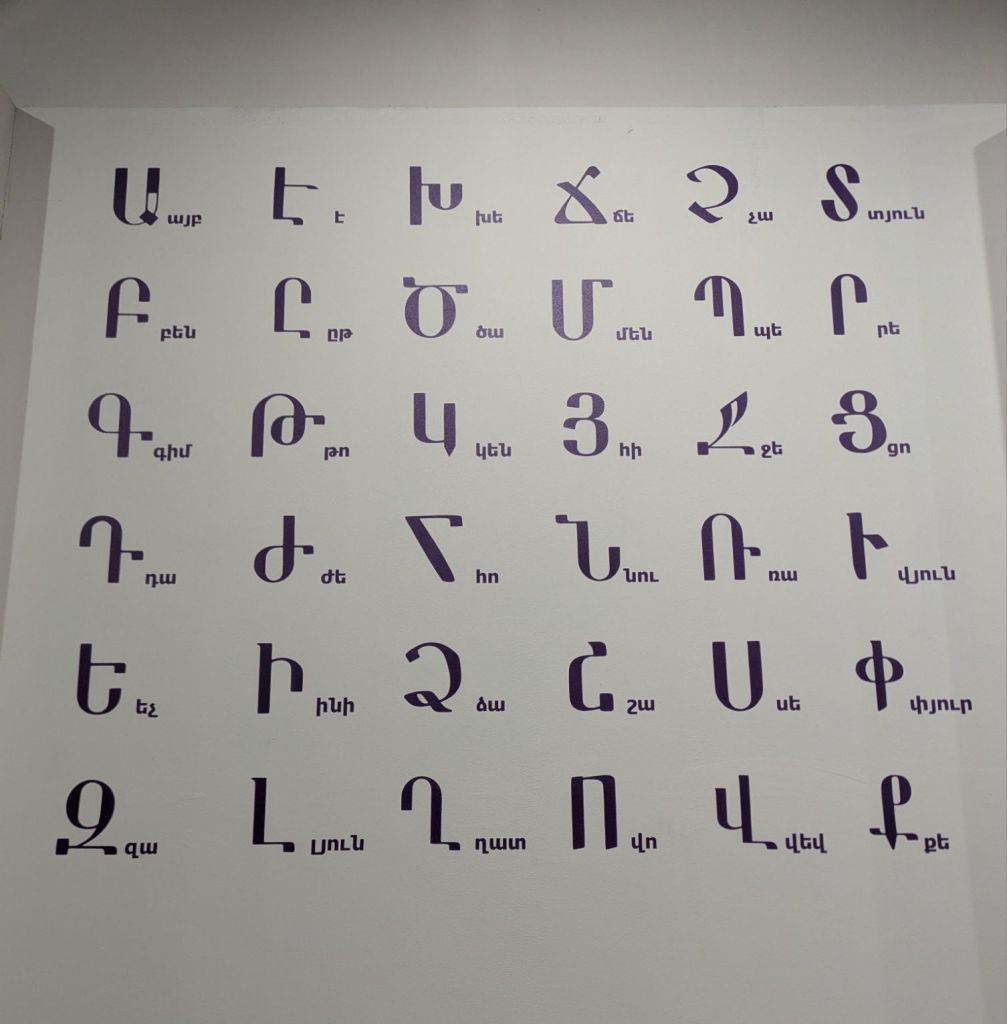

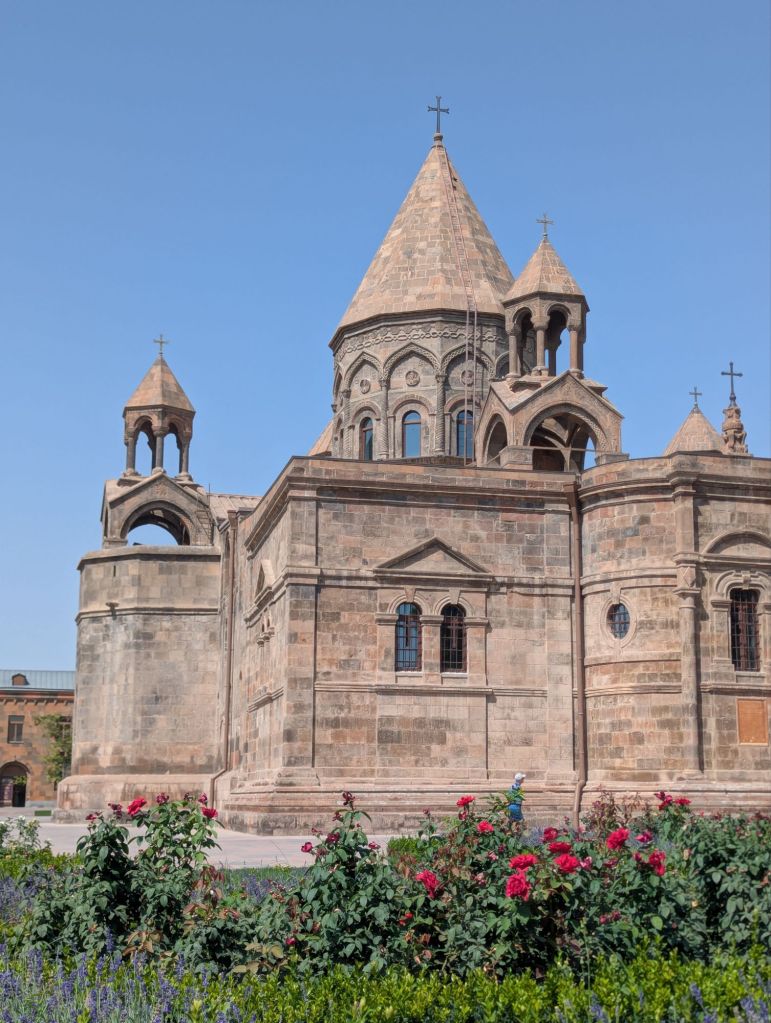

An Irishman I’d been sipping tea with back in Çayloveyou café asked if I planned to visit Ani – an abandoned Armenian city about 40km east of Kars. The fact that this part of Ottoman Turkey had a thriving Armenian community until the genocide had rarely been far from the forefront of my mind since entering Turkey, the landscape is more or less identical to the Armenian Highlands but the society is thoroughly Turkified. Even though Ani had been abandoned for centuries by 1915, the prospect of walking around an entire city in ruins felt like one visual metaphor step too far for me.

There would be no trip to Ani on this trip then. Instead, the plan was to briefly head north again to get out of Kars and follow the back roads until I reached the D060, then start heading west towards the town of Göle.

A rocky police encounter

Following the breadcrumbs on my satnav, I weaved past a strategically placed block of reinforced concrete in the centre of the road and slowly made my way up a painfully steep bank. It hadn’t quite twigged yet, but there was a stark contrast emerging between the lush green gardens of the fenced-off detached residences to my left and the wasteland of broken concrete and dumped rubbish I was cycling through. A young alsatian was bouncing up and down on its hind legs from behind the tall metal perimeter fence, and its police officer handler gestured that I should come through the electronic gate into the compound.

“We were surprised to see you there, that road is closed. Nobody uses that road.”

“It’s closed? Oh, erm…üzgünüm?!“

Still unsure if I was in bother or not, it seemed wiser to apologise rather than get into an argument about the need for clear signage in such circumstances.

It soon became clear I was in no trouble at all when the chai began to flow and I was presented with a salted baked potato with a core temperature approaching ideal conditions for nuclear fusion. The compound contained lodgings for senior military staff based at the nearby barracks, and guarding the place seemed to involve an awful lot of not a lot, where impromptu conversations with fluorescently clad Brits can break up the day nicely. Learning I studied geology, the younger cop went into the gatehouse and returned with a glossy black lump of volcanic glass.

“Obsidian, from this region“, he explained whilst placing the stone into my hand. Completely failing to explain in my customary mish-mash of Turkish, English and body language that lumps of rock are a bit too heavy to carry home as a souvenir, I popped it in the handlebar bag and waved my new friends farewell.

How many dogs is too many dogs?

The road out of Kars was a single carriageway that slowly wound its way into progressively more and more remote countryside. This is sheep farming country, where the jingle jangle of bells is an integral part of the soundscape as the shepherds lead their flocks up and down the hills in the endless search for good grazing.

There are farms too of course, typically quite small and family-run, often spaced within only a stone’s throw of one another. With farms come farm dogs, and they were in no short supply in this particular corner of Turkey. After a few relatively ‘easy’ encounters where the dogs barked at me but never really got close, the route deviated off the ‘main’ road up towards a remote looking valley, where just beside the road on the right hand side there was a farmyard.

There were four dogs that I could actually see, with one particular mutt (Psycho) appearing twice from different angles in the collage above. To find yourself completely surrounded by barking dogs is quite an unnerving experience, but it didn’t take long to tune into the group dynamics and conclude that the risk of becoming Pedigree chum was actually quite low.

- Dopey, stranded in the long grass like a wind-fallen lemon was wagging its tale and just seemed happy to be part of the action.

- Weenus was following me but very half-heartedly, and soon gave up. No passion, no commitment.

- Psycho was showing the real aggression, and it wasn’t even a Kangal (Akbash are the second most common shepherd dogs in Turkey). Being held back by a metal chain, it’s hard to know whether the obscene bloodlust on display would have sustained had the chain snapped and it could actually reach me.

- Stalker was the most persistent mutt of the pack, naturally. A fairly young Kangal, Stalker continued to follow and bark at me for the best part of two minutes. It wasn’t until I stopped dead and lunged in its general direction that the stalking desisted and no restraining order was required.

Although it never really felt like I was in serious danger, having to deal with so many unleashed, powerful dogs that are trained from birth to intimidate strangers was beginning to become quite tiring…and this was only the second full day of cycling in Turkey! But this was a particularly rural section of hill farms and tiny villages, surely the main roads will be more sheltered in this regard, surely!?

Come for the chai, stay for the chicken

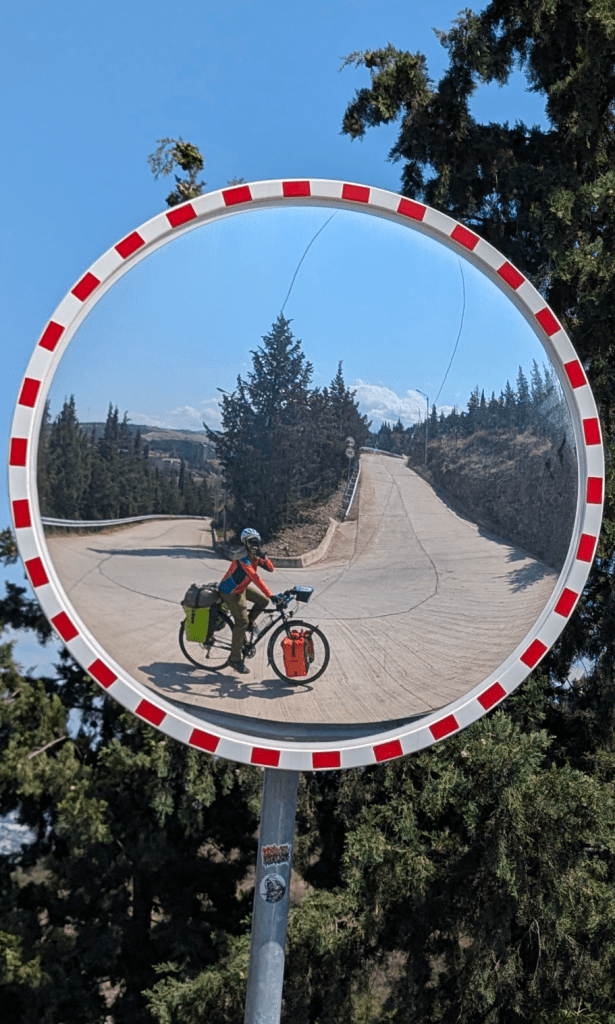

The road was now becoming a gravel path as it zig-zagged up the hillside towards a small lake. I passed through Gölbaşı – one of countless tiny farming communities in the region where residents scrape out a living from sheep farming, beekeeping and whatever else they can squeeze out of the arid land at over 2,100m above sea level.

Still in my saddle but riding slowly, an elderly man stood in the garden of his white bungalow caught my eye and waved at me to come over. In stark contrast to being castigated by a pack of territorial dogs, this was the warm & hospitable side of Turkey. Anticipating a cup of tea, my expectations were blown away when a plate of roast chicken, bread, honey and cheese was served up by his wife, who vanished back into the cottage as quickly as she had appeared.

A small flock of ducks huddled beneath a leaking tap to paddle and sip from the puddle below; a very pregnant Border Collie wandered into the garden and lay down to watch me eat the roast chicken, with hopeful eyes.

“Not my dog, village dog.”

Gölbaşı was totally serene that evening. The breeze had succumbed to stillness, and the setting sun was painting the hillsides with warm shades of amber, burnt orange and pink. I said my goodbyes to the man and his wife and began the search for a camping spot. I headed for the slightly busier road to Göle, where after a few kilometres I came across some flat ground not far from the road but just about out of view of passing traffic. By 10pm the hillsides were deserted, leaving just the hum of insects interspersed by the faint barking of dogs from a village up the road.

At this altitude with clear skies it was going to be a chilly night; thankfully, a previous plan to send all my cold weather clothing home in a parcel when I got to Azerbaijan had been scuppered by an aversion to the faff of international post. I put on my merino wool pyjamas, cotton jogging bottoms, synthetic fleece, and laid my down jacket on top of the sleeping bag like a blanket…cosy even at 3°C.

———————————

PHOTOGRAPHY: Kars